Checkpointing and Consistent Recovery Lines: Handling Failure in Wallaroo

When you’re working with distributed systems, you need to take seriously the possibility of failure. Since streaming systems like Wallaroo can be left running for days, weeks, or even years, you’re basically guaranteed to encounter failure.

Ideally, whenever something fails, you’d be able to recover your system and pick up from where you left off before things went wrong, all without message loss.

We added support for asynchronous checkpointing to Wallaroo as part of the 0.5.3 release↗(opens in a new tab). A checkpoint is a kind of periodic global snapshot of Wallaroo state. With checkpoints, Wallaroo clusters can respond to failure by rolling the system back to the most recent valid global state, at which point they can continue processing.

We use a barrier algorithm based on the Chandy-Lamport algorithm↗(opens in a new tab) and some of the modifications proposed in “Lightweight Asynchronous Snapshots for Distributed Dataflows”↗(opens in a new tab). The advantage of this algorithm (first implemented in Apache Flink) is that it ensures consistent checkpoints while adding relatively little overhead, and without the need to stop processing globally.

In this blog post, I’m going to explain some of the challenges around recovering to a valid global state. I’ll talk about a couple of ways that you could approach this problem, and explain why the asynchronous checkpointing algorithm we’ve adopted is a great fit for stream processing systems. Finally, I’ll talk a bit about how this algorithm is implemented in Wallaroo in particular.

The aim of this post is to show you some of the key issues we considered when choosing how to handle failure in our system, and, in the process, introduce you to some concepts and resources that will help you in thinking about how to build resilient distributed systems of your own.

Consistent and Inconsistent Recovery Lines

It’s important that after failure, a distributed system recovers to a valid state. But what does this mean? In the distributed systems literature, this is often framed in terms of causal consistency. In A Survey of Rollback-Recovery Protocols in Message-Passing Systems↗(opens in a new tab), we find the following definition:

Intuitively, a consistent global state is one that may occur during a failure-free, correct execution of a distributed computation. More precisely, a consistent system state is one in which if a process’s state reflects a message receipt, then the state of the corresponding sender reflects sending that message.

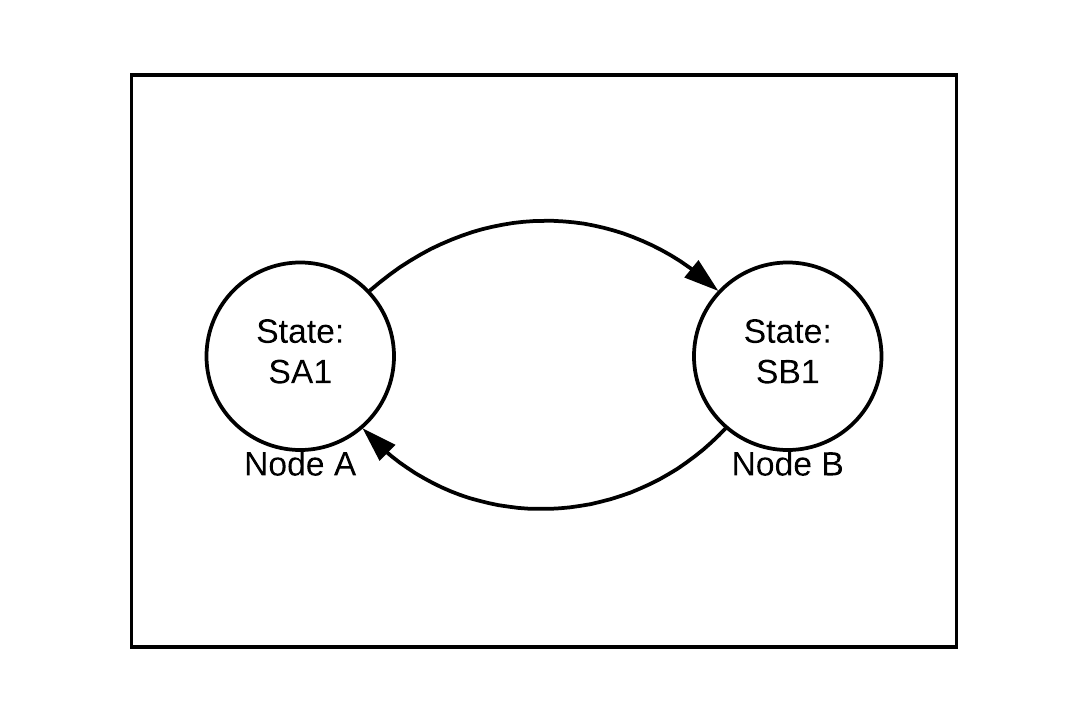

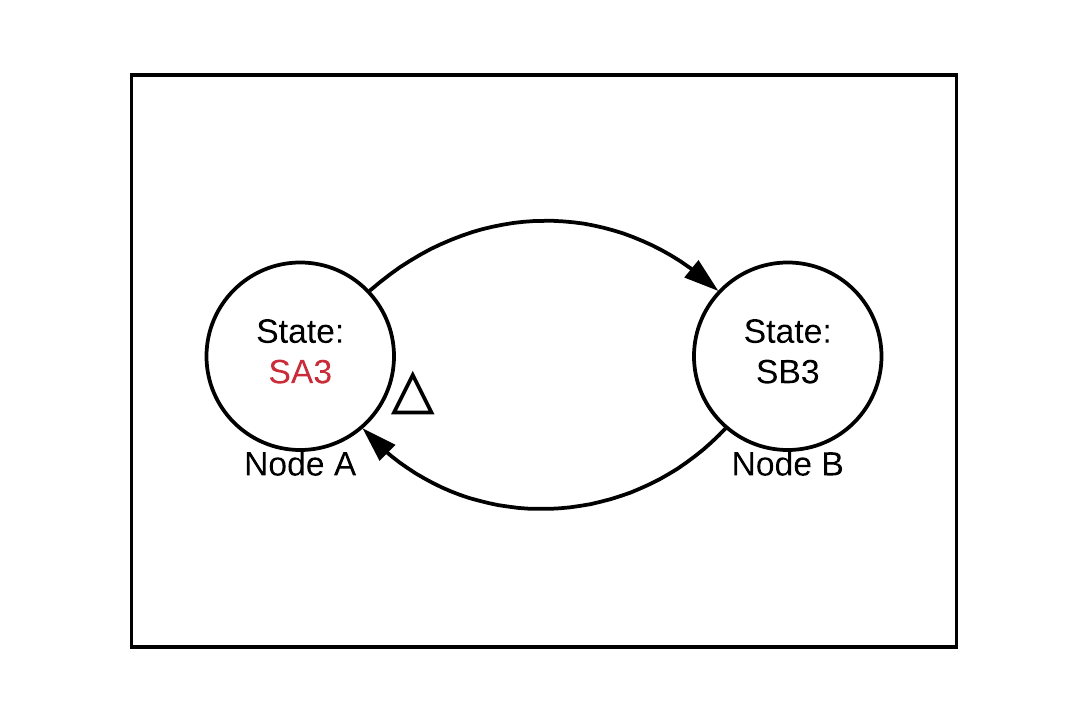

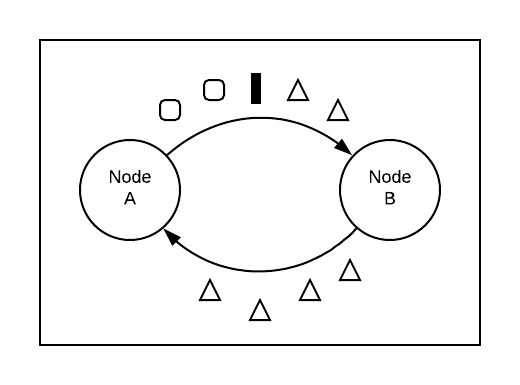

In order to understand this more clearly, let’s look at a simple distributed system composed of two nodes, A and B:

The circles represent the nodes, with A initially in state SA1 and B initially in state SB1. The arrows represent directed channels between the nodes over which messages can be sent. Let’s trace a possible execution history for this small system.

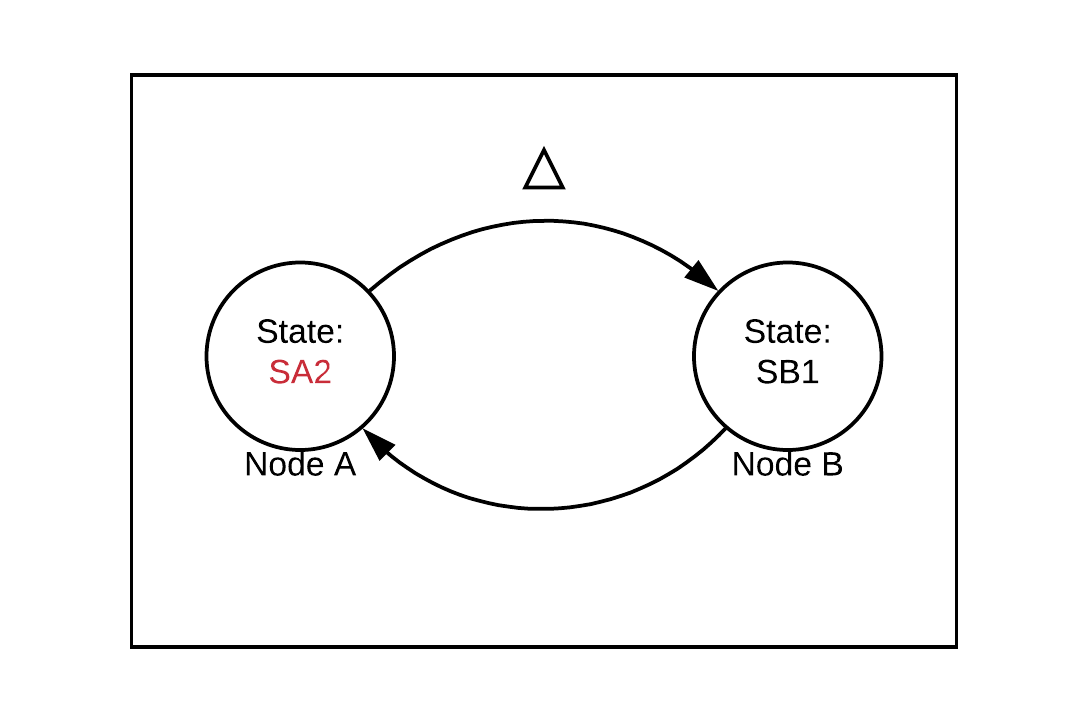

First, node A sends a message to node B, transitioning to state SA2 in the process:

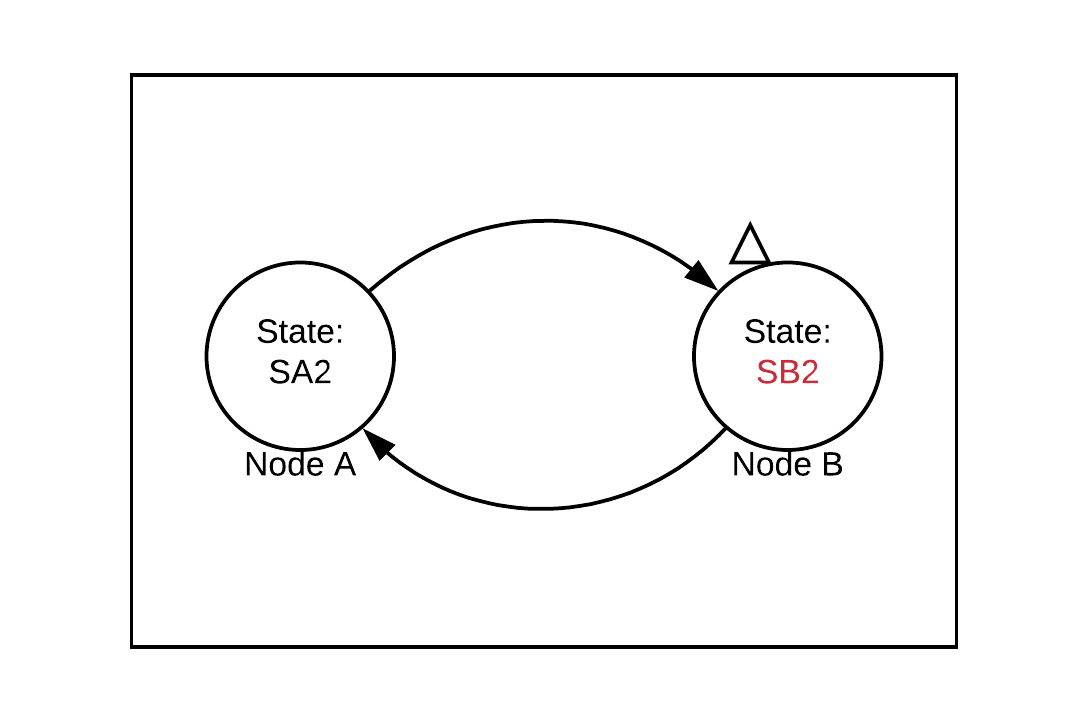

Node B then updates its state to SB2 in response to this message:

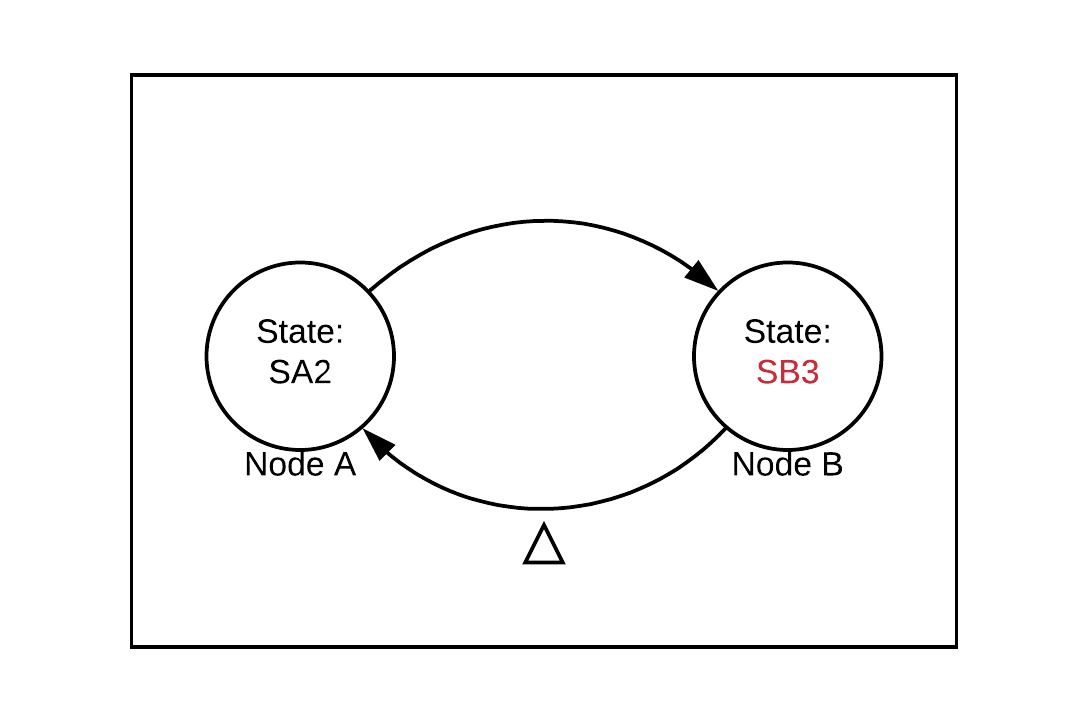

Next, node B sends a message to node A and transitions to state SB3:

Then, node A updates its state to SA3 in response to the reply:

Finally, we’ll imagine that node B fails at this point.

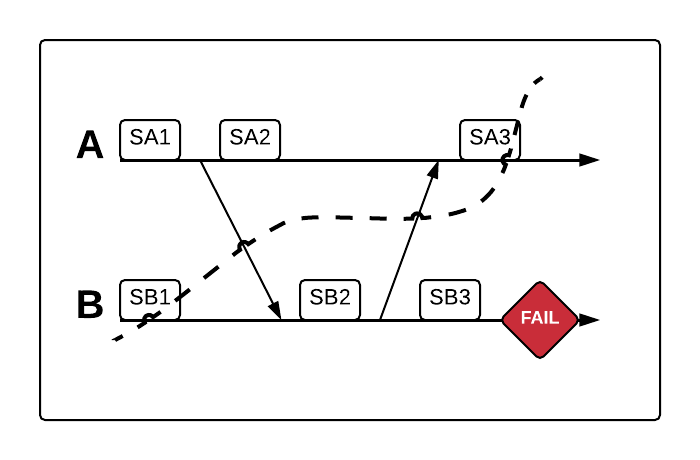

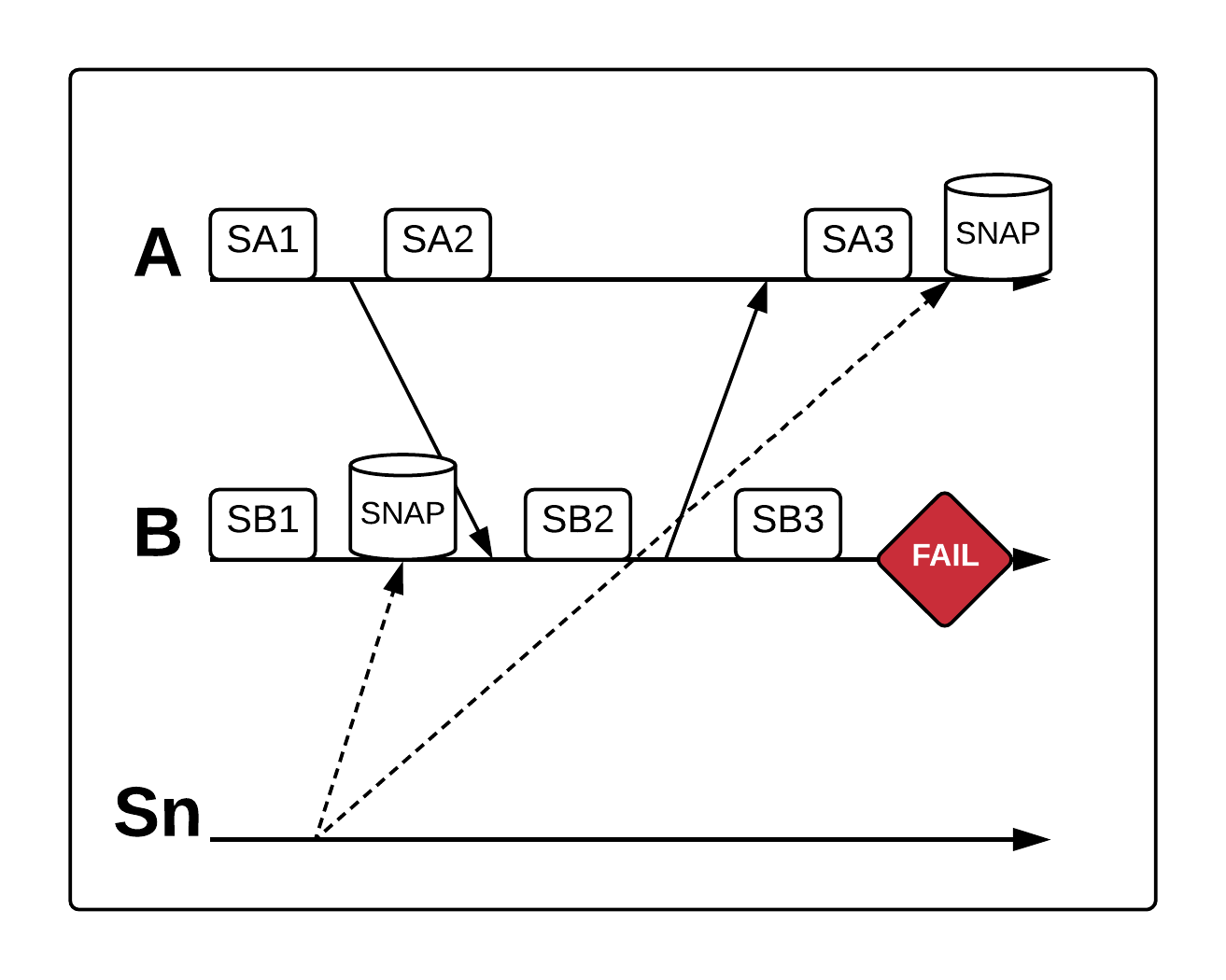

We can diagram this entire process using horizontal lines to represent the execution histories of the nodes in the system, arrows between these lines to represent message sends between nodes, squares to represent state changes on a node, and a red diamond to represent failure:

Imagine that node B fails at the point indicated in the diagram. We can’t simply reinitialize node B to its initial state SB1. That’s because the state change on node A from SA2 to SA3 is ultimately an effect of the message sent from node B when it was in state SB2.

You can see this by following the arrows between node lines. There is no execution that could have led to a configuration where node A is in state SA3 and node B is in SB1.

We can draw a line through our diagram, called a recovery line, to check whether the configuration of states we just described adds up to a consistent global state. A recovery line runs through every state in the configuration, and represents the set of states we are recovering to:

Notice that A shows the receipt of a message from B behind the recovery line, but the send of that same message from B is past the recovery line. This is a causally inconsistent global state.

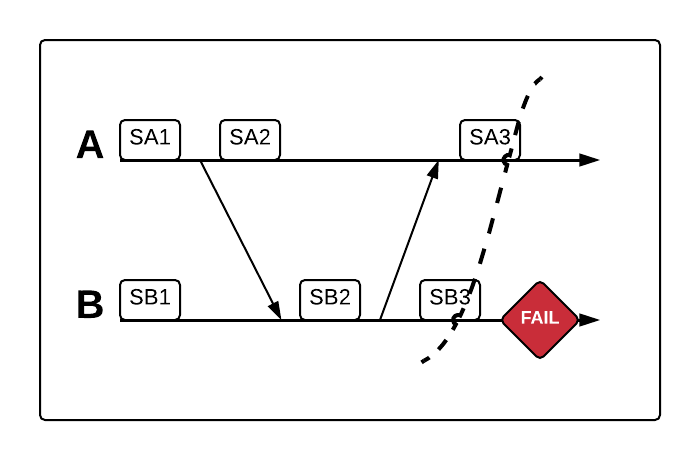

In this case, we either need to roll A back to its initial state as well (which means we’d have to start all processing from the beginning) or we need B to recover to SB3, which would produce the following consistent recovery line:

Rolling both A and B back to SA2 and SB2 respectively would also produce a consistent recovery line. The important point is that every message receipt has its corresponding message send behind the line:

Snapshotting State

In order to roll our nodes back to earlier states, we need to take snapshots of that state that can be written to persistent storage. Let’s start with a naive approach where we periodically have every node in the system snapshot its current state to disk. Then, when it’s time to recover, we simply tell every node to roll back to the last state it snapshotted.

Let’s consider two ways we might implement this naive approach. First, we could send a snapshot command to every node at a certain frequency, say every minute. Or, second, we could have every node independently take a snapshot at a certain frequency, say every minute on the minute.

If we were to attempt either of these, it wouldn’t be long before we discovered that there is no now↗(opens in a new tab) in a distributed system. The first approach ignores the fact that the snapshot command might arrive at various nodes at different times. The second approach ignores the existence of clock skew across nodes in distributed systems. Clock skew implies that “on the minute” on one node does not necessarily happen simultaneously with “on the minute” on another node.

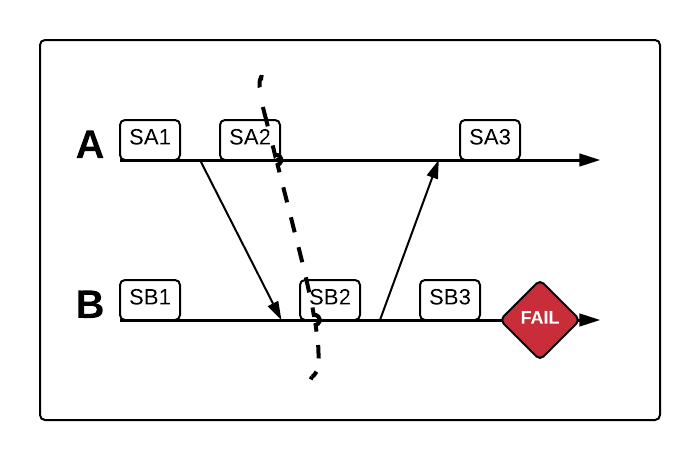

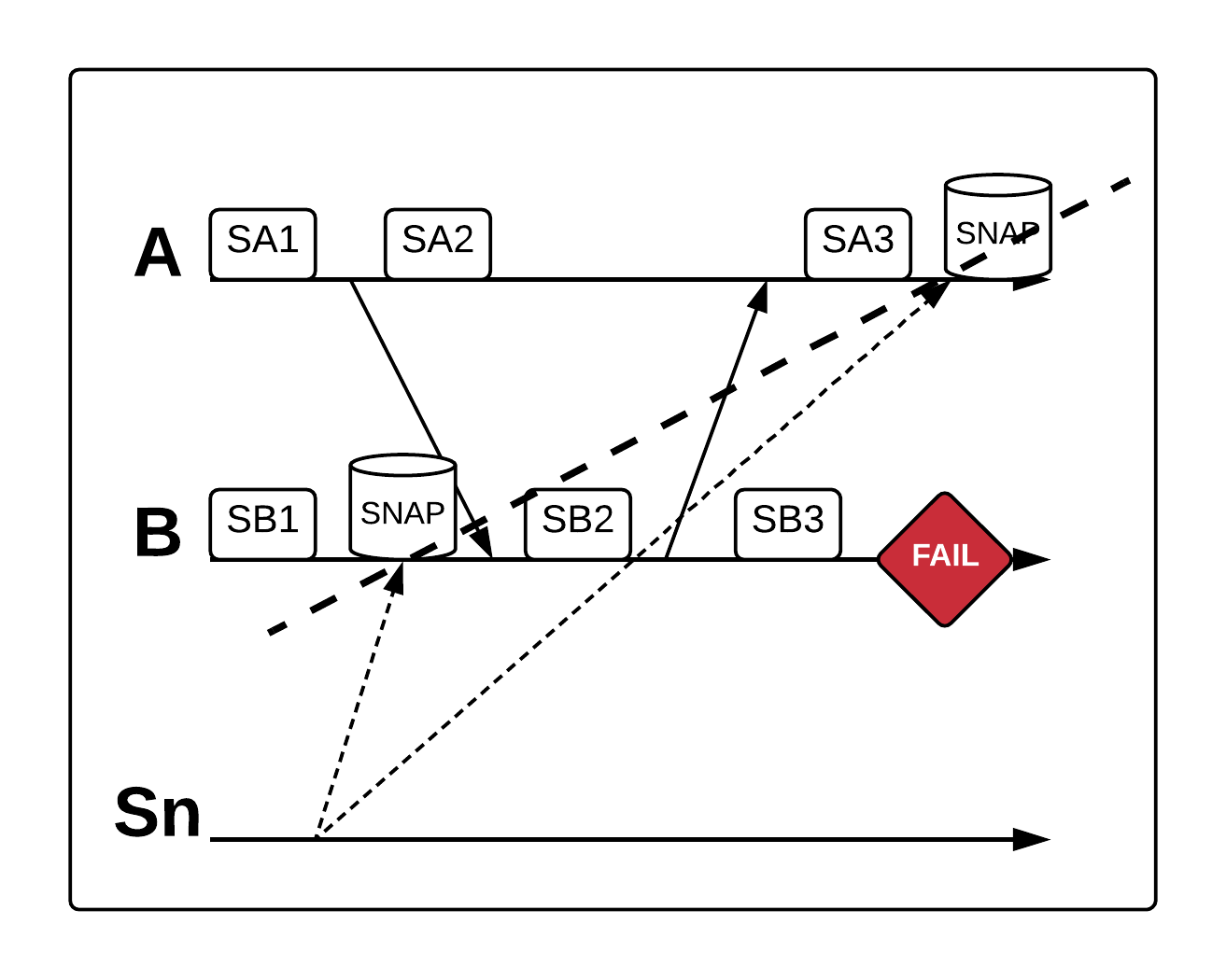

Sticking with our two-node system, the following diagram shows one way things can go wrong (note that we’ve added a new line labeled “Sn” to indicate a node that sends snapshot commands to the other nodes):

If the snapshot command arrives at node A later than node B, then node B might snapshot while still in its initial state SB1. It might then receive a message from A, update its state, and send a reply to A, all before A thinks it’s time to snapshot. A might receive the reply from B, update its own state to SA3, and only then receive the snapshot command (writing SA3 to disk).

The result? If we tried to recover using those two local snapshots, we would end up in exactly the impossible configuration we discussed above (with B in SB1 and A in SA3). The resulting inconsistent recovery line would look like this:

There is another way things can go wrong here, even if we manage by chance to land on a consistent recovery line. Imagine that A receives the snapshot command immediately after transitioning to SA2 and B receives the command after transitioning to SB3. This produces the following consistent recovery line:

This diagram illustrates a consistent global state because there is no message receipt behind the recovery line that lacks a corresponding message send. However, in this case, we have a message send behind the line that lacks a corresponding receipt. In practice, this means message loss.

When we recover to SB3 on node B, it will not send its message again (assuming we have not devised a way to deal with this kind of scenario). This means node A will never receive the message, since we rolled it back to SA2, which does not reflect that message receipt. Ensuring a consistent recovery line is part of a successful strategy for handling failure, but we must also address the possibility of message loss.

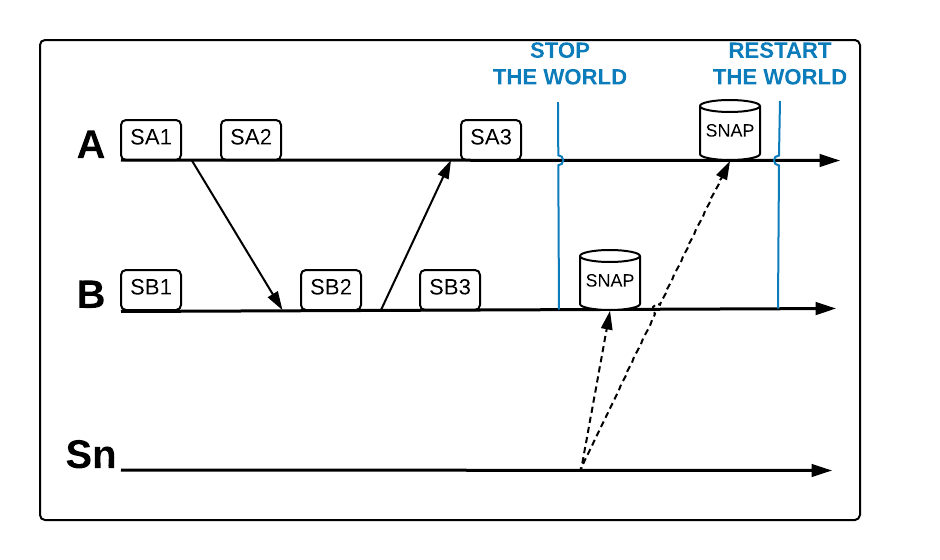

So how do we deal with the kind of timing problems described above? Perhaps the most straightforward way is to stop the world before attempting a global snapshot. If we could stop all activity in the system and only then tell every node to snapshot, we should be able to get a consistent snapshot across nodes.

When nothing is happening in the system, the order in which different nodes receive a snapshot command shouldn’t matter (as long as they all receive it before processing restarts). We can illustrate this strategy as follows:

In practice, however, this means we require a high degree of coordination and incur a significant performance cost because of the need to stop processing for however long the snapshots take.

Reducing Coordination with Barrier Algorithms

The Chandy-Lamport snapshot algorithm↗(opens in a new tab) provides one way to avoid this kind of coordination. One of the goals of this algorithm is for snapshotting to run concurrently with the underlying computation without impacting it. In other words, with Chandy-Lamport, we get consistent global snapshots without having to stop processing.

A consistent global snapshot allows us to roll back a distributed system to a consistent recovery line. For any global snapshot, we can partition all the events in the history of the system (including message sends and receives) into events that happened before the snapshot and events that happened after the snapshot. The recovery line represents the boundary between these two partitions.

The naïve approach could not reliably partition events into the correct sides of this boundary, as evidenced by the inconsistent recovery line illustrated in the last section. The stop-the-world approach succeeded by stopping all activity, which is perhaps the most straightforward way to do the partitioning: every event that happened before the stop-the-world pause counts as part of the snapshot, and every event that will happen once we restart the world counts as part of future snapshots. But this comes at a significant performance cost.

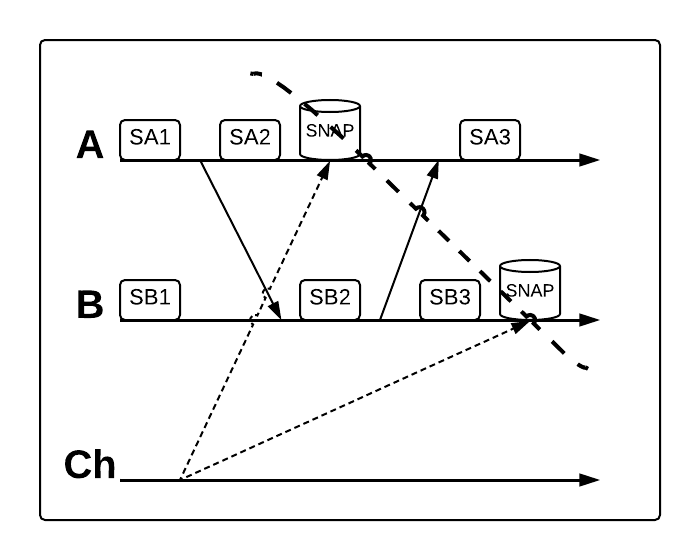

Assuming that channels between nodes are reliable and FIFO (first in, first out), Chandy-Lamport achieves the correct partitioning by injecting a special barrier marker into the flow of messages through the system. In our simple two node system, imagine that node A initiates the snapshot after some amount of processing has taken place. B will have received some number of messages from A before A sends along a barrier.

This barrier represents the boundary between the current snapshot and the next one. Every message B received before the barrier is related to the current snapshot (represented by triangles in the diagram below). Every message it receives from A after the barrier is related to future snapshots (represented by squares):

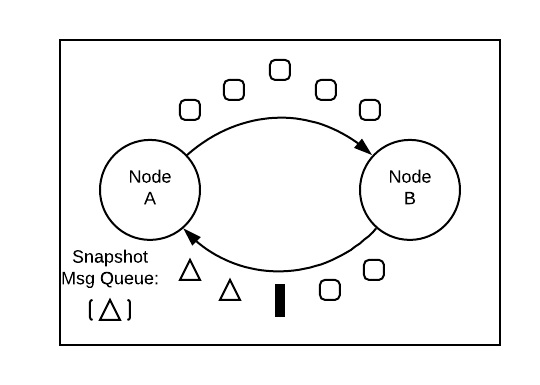

When B receives a barrier, it snapshots its local state and forwards the barrier along all its outputs (in this case it only has the one output to A). A then reasons in the same way. All the messages it received from B before the barrier are related to the current snapshot.

After initiating the barrier, A queues all messages from B until it receives a barrier from B. All the messages it receives after the barrier are related to future snapshots:

Once a node has received barriers over all its inputs, it’s free to write its local snapshot to disk. With the Chandy-Lamport algorithm, this local snapshot will include more than just the node’s local state.

Once a node either initiates or first receives a barrier for a given snapshot, it must add any pre-barrier messages it subsequently receives over any other inputs to the snapshot. Otherwise, they will be lost on recovery.

In the diagram above, from the point that A initiates the barrier, it has to queue any messages it receives over the input from B until it receives the barrier over that input. B, on the other hand, never queues messages because it received the barrier over its one and only input (and did not initiate it). If B had a second input, say from a node C, then after receiving the barrier from A, it would have to start queueing messages from C until it receives the barrier from C.

Notice that on this approach a node never has to stop processing messages, thus avoiding the costs associated with the stop-the-world approach. With Chandy-Lamport, the message queue is only for writing those messages to disk with the snapshot. You can actually just keep copies in the queue and process those messages immediately. The important thing is that outputs corresponding to those messages will only be sent after the barrier.

Checkpointing in a Stream Processing System

One of the requirements of the Chandy-Lamport algorithm is that the graph of nodes in the system must be strongly connected. This means there must be a path from any node to any other node (this requirement is clearly met in our two-node example). Otherwise the barriers wouldn’t be able to propagate to all nodes and the global snapshot wouldn’t include every part of the system.

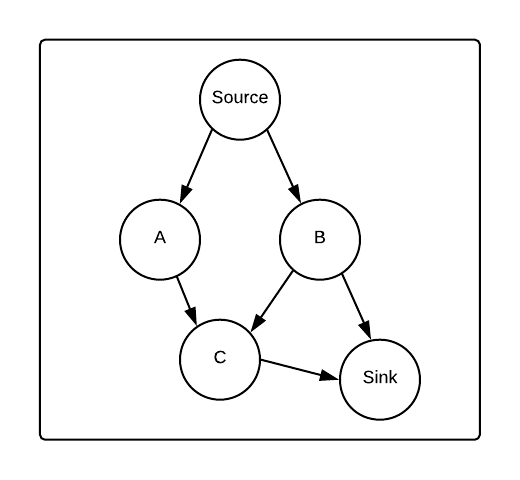

But streaming data processors like Wallaroo use weakly connected graphs. That’s because they involve data pipelines that begin at sources and normally run through directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) down to sinks. For example, consider the following graph:

If a barrier were initiated at node B, the barriers it emitted would never reach the source–since there are no paths from B to the source–and thus the source wouldn’t be included in the global snapshot. Of course, the barrier wouldn’t reach A either, since there is also no path from B to A. Only B, C, and the sink would take part in the snapshot algorithm.

In “Lightweight Asynchronous Barrier Snapshots”↗(opens in a new tab), Paris Carbone et al. show that in the case of a DAG, with some minor modifications to Chandy-Lamport, you can take local snapshots without having to include data about in-flight messages and still avoid message loss.

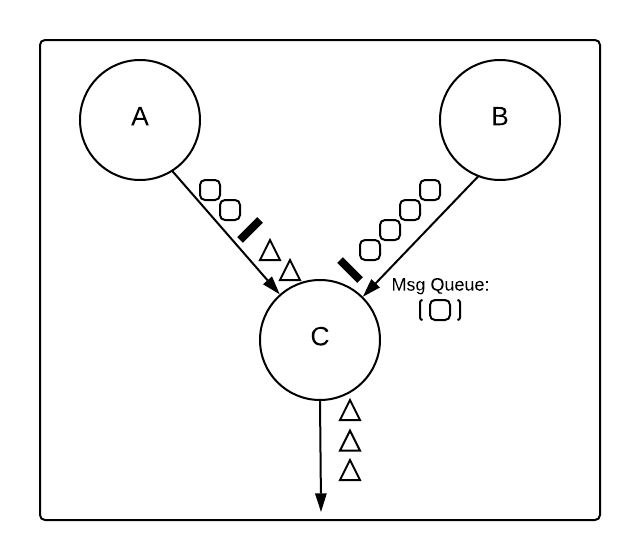

As illustrated by the last example, you must inject barriers at the sources, since otherwise they won’t reach all nodes in the graph. Those barriers then propagate down the DAG. When a node receives a barrier over an input, it temporarily blocks that input, queuing any messages it receives over it.

Those queued messages are treated as part of the next snapshot, not the current one designated by the current barrier. The following diagram illustrates how this might happen at a node with two inputs:

Once C receives the barrier from B, it blocks that input, adding messages related to the next snapshot (the squares) to a queue. Meanwhile, it continues processing messages related to the current snapshot that it receives from A (the triangles).

Queueing here is in a sense the opposite of in the unmodified Chandy-Lamport algorithm: a node can’t process the queued messages until it’s received the barrier over all its inputs, but it also doesn’t need to write them to disk with the snapshot.

Once a node has received the barrier over all of its inputs, it’s free to snapshot its local state and send the barrier along over all of its outputs. It can then immediately flush its input queues and begin processing like normal again until it receives a barrier for the next snapshot.

Notice that any message it sends out over an output at this point will come after the barrier it has sent on that output, thereby maintaining the correct partitioning. There is a latency cost to the temporary queuing on the inputs, but on the other hand you no longer need to write messages received before a barrier to disk as part of the snapshot.

A global snapshot taken using this modified Chandy-Lamport algorithm is called a checkpoint. The barriers partition messages into those associated with one checkpoint and those associated with the next. The checkpoint acts as a consistent recovery line, a global state that you can safely roll back to when recovering from failure.

Assuming that all processing is message-driven (as is true in stream processing systems like Wallaroo), the barriers also guard against message loss. This is because any pre-barrier message sent by a node will already be received and processed by the receiving node before it gets the barrier. Consequently, the local snapshot for that barrier will reflect the receipt of all pre-barrier messages. There will never be a recovery line that reflects a message send but no corresponding message receipt.

Wallaroo’s actor-based implementation

Wallaroo is implemented in the actor-based Pony programming language↗(opens in a new tab). This means that a Wallaroo execution graph consists of actors distributed over one or more UNIX processes. Actors communicate with each other asynchronously by passing messages.

On a single process, the Pony runtime provides ordering, reliability, and FIFO guarantees for messages sent from one actor to another. Wallaroo also includes infrastructure that allows actors to pass messages to each other across process boundaries over TCP connections.

A combination of TCP reliable delivery guarantees and Wallaroo infrastructure (which checks that messages are received in sequence and without gaps over the network) means that point-to-point connections between actors over the network are also FIFO. This is important because the barrier algorithm described above depends on reliable FIFO channels.

Based on a configurable interval, Wallaroo periodically initiates checkpoints by having a checkpoint initiator inject barriers at all source actors. These source actors snapshot their local state and then forward the barrier along all their outputs.

Downstream actors follow the modified Chandy-Lamport algorithm described above, blocking on inputs on which a barrier has arrived until they’ve received barriers over all inputs, at which point they also snapshot their local state and forward the barrier down their outputs. Once all sink actors receive their barriers and snapshot local state, they send acks to the checkpoint initiator, which triggers the checkpoint commit.

On recovery from failure, the system rolls back to the last checkpoint that was successfully committed. The sources are then free to request replay from upstreams, starting immediately after the last message they received as part of the checkpoint they rolled back to. At this point Wallaroo resumes normal processing.

If all Wallaroo consumers can participate in 2 phase commit (or if, given some caveats, they ensure idempotence), then our checkpoints can be used to support effectively-once semantics.